Published by Margaret Balwierz

Dissection of the Fabrica and Anatomical History

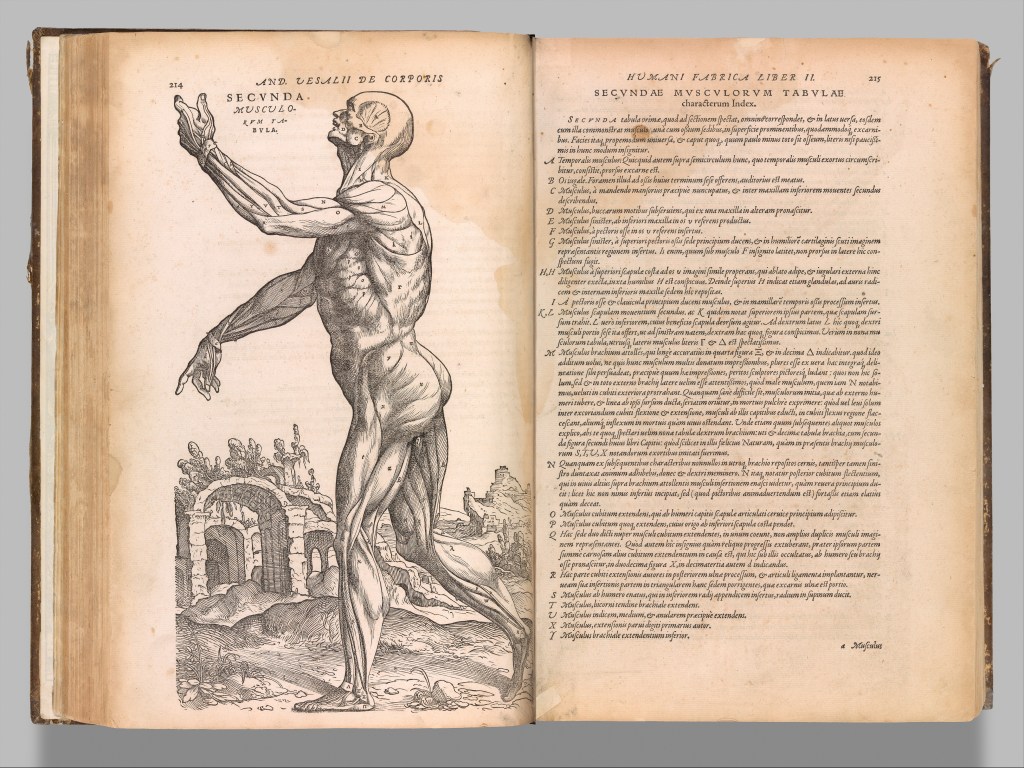

Four hundred years after the De humani corporis fabrica was published, Nolie Mumey wrote Quatercentenary of the Publication of Scientific Anatomy, 1543-1943, in praise of the groundbreaking seven-volume anatomical text. Mumey, who donated this book to the collection, was a doctor and author who was interested in history, so his exploration of the Fabrica is multi-faceted. In this text, he discusses the production of the Fabrica, as well as the text and artwork itself. Reproductions of the original woodcuts are included in Mumey’s book, showcasing the skill of the artists in not only decorative art but anatomical art as well. Mumey also touches on the impact of the descriptions of the anatomical systems, pointing out the inaccuracies they contain. He does not, however, discuss the ethical implications of human dissection, which made this work possible.

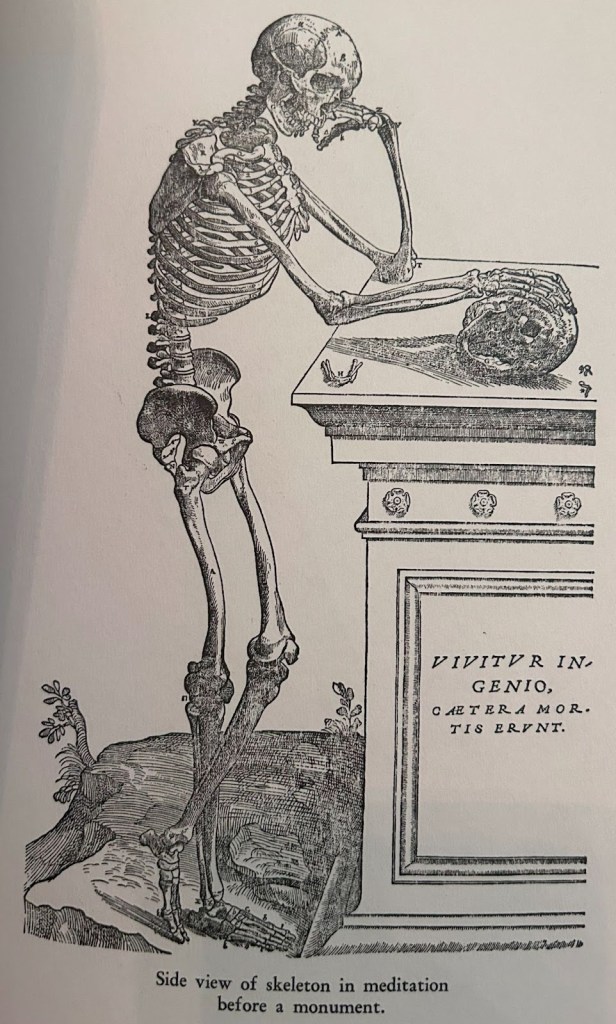

The Fabrica was created by Andreas Vesalius along with the help of artists believed to be Jan Steven van Calcar, Joannes Stephanus, and Nicolo Stupio (Mumey, 1944, p. 41). On the third floor of the Museum in the Anatomical Illustration exhibit, there is a reproduction of Jan Steven van Calcar’s Portrait of Andreas Vesalius (IMSS, Floor 3, Anatomical Illustration room, Item 4). These artists created drawings made into plates to engrave the images in the book (Mumey, 1944, p. 23). They worked with Vesalius, whose dissections informed the depictions of the various anatomical systems. The figures that these artists rendered, most notably the skeletons and musclemen, are posed in a variety of ways to showcase the different systems and movements. This is combined with Vesalius’s notes describing the specific bones, muscles, or veins to give a detailed picture of the human body.

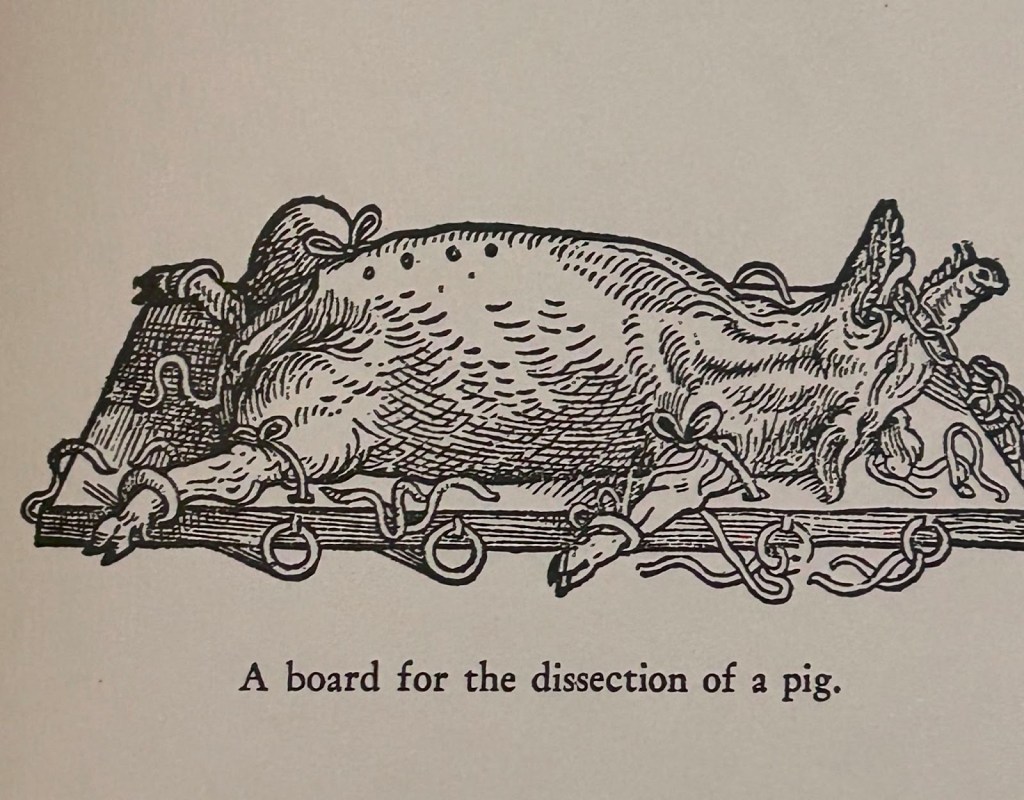

Andres Vesalius was interested in learning about the human body but was frustrated attempting to learn from existing anatomical texts. The predominant authority on anatomy at the time was Galen’s work, which was created over a millennia before. This work was based on the dissection of animals, not humans, so it was not completely accurate (Mumey, 1944, p. 18). Vesalius initially started with dissecting animals as well but then began dissecting humans. Traditionally these were performed by barber-surgeons, not anatomists themselves, but by doing these himself, Vesalius had a better understanding of the human body. Through this shift, he could set a precedent of anatomists learning through hands-on experience, rather than regurgitating and reciting existing knowledge which was not always accurate.

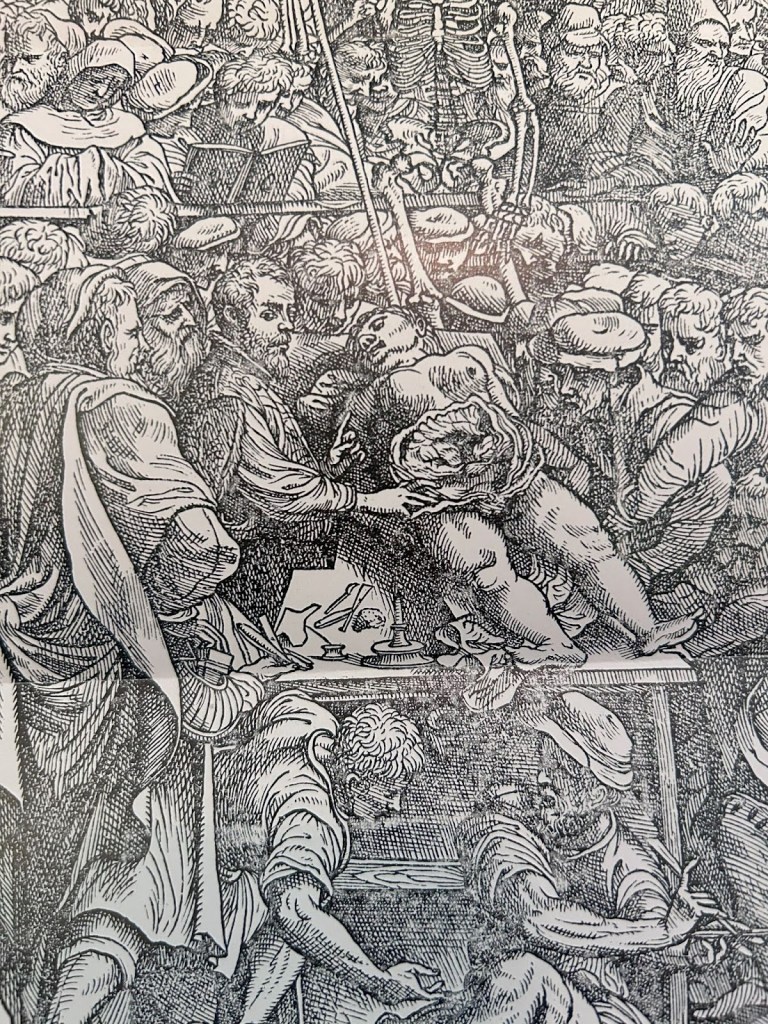

Eventually, dissections were performed in places like the University of Padua’s anatomical theater, where Andres Vesalius taught. This caused a rise in the need for human bodies to use in these dissections beyond the typical legal ways of procurement. Vesalius resorted to stealing the bodies of people who had been executed to be able to learn about the human body through dissection (Ghosh, 2015, p. 158). Human dissections were more common and acceptable during Vesalius’ life, although there were still legal and ethical issues surrounding the procurement of human cadavers.

Throughout various cultures, there are moral, ethical, and religious objections to human dissection. Governments typically allowed the dissection of people who were sentenced to death, but when there were not enough bodies for the medical schools, laws in some areas adjusted to make more offenses punishable by death. Rules were also changed to allow anatomists to procure the bodies of the poor or unclaimed, the mentally ill, slaves, and prisoners (Ghosh, 2015, pp. 161-162). These are people who could not consent to the use of their bodies to advance this scientific knowledge. Unfortunately, when medical history is discussed, a lot of it rests on dubious practices, so there should be an acknowledgment of the practices.

Coincidentally, while Nolie Mumey writes this volume in the adulation of the Fabrica, another anatomical text, Pernkopf’s Atlas, is recently published in Nazi Germany. This particular book is controversial due to the use of people who were prisoners of the concentration camps. “Historical incidents like these should serve as a reminder for present day anatomists that disregard of moral values cannot be justified by the quest for scientific glory. Rather being members of the medical profession we should premiere the cause of ethical considerations in the scientific activities that we undertake” (Ghosh, 2015, p. 162). This has prompted stricter laws and regulations since Vesalius’ time about informed consent and the use of humans in scientific exploration.

Currently, in the United States and many other countries, anatomy is practiced on humans who have donated their bodies for the express purpose of study. Students are taught to give respect to the human lives, with the performance of memorials and funerals for the deceased (Ghosh, 2015, pp. 163-164). While there is now reverence for the human lives given, as a society, respect should also be given to the unknown and unnamed people whose bodies were used without consent in the advancement of knowledge.

Works Cited:

(Sixteenth Century) Reproduction of Jan Steven’s Portrait of Andreas Vesalius. On-site at the International Museum of Surgical Science, Third Floor, Anatomical Illustration Room, Item number 4

Ghosh, S. K. (2015). Human cadaveric dissection: A historical account from Ancient Greece to the modern era. Anatomy & Cell Biology,48(3), 153-169. doi:10.5115/acb.2015.48.3.153

Model of Anatomical Theatre, University of Padua, 1/8 Scale. On-site at the International Museum of Surgical Science, Third Floor, Anatomical Illustration Room, Item number 7

Mumey, N. (1944). Quatercentenary of the Publication of Scientific Anatomy, 1543-1943. Denver, CO: Range Press. IMSS Catalog #06-03-05

Soth, A. (2019, January 24). Public dissection was a gruesome spectacle – JSTOR daily. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://daily.jstor.org/public-dissection-gruesome-spectacle/

Vesalius, A. (1555). De humani corporis fabrica. From The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession Number: 53.682 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/358129

Margaret Balwierz was the Spring 2023 Library Intern at the International Museum of Surgical Science. She is currently working on her Master’s of Library and Information Science at Dominican University. Margaret enjoys learning about medical history and the ethics surrounding medicine and death. She also enjoys art and relaxing in nature.