February 19, 2016 – March 5, 2017

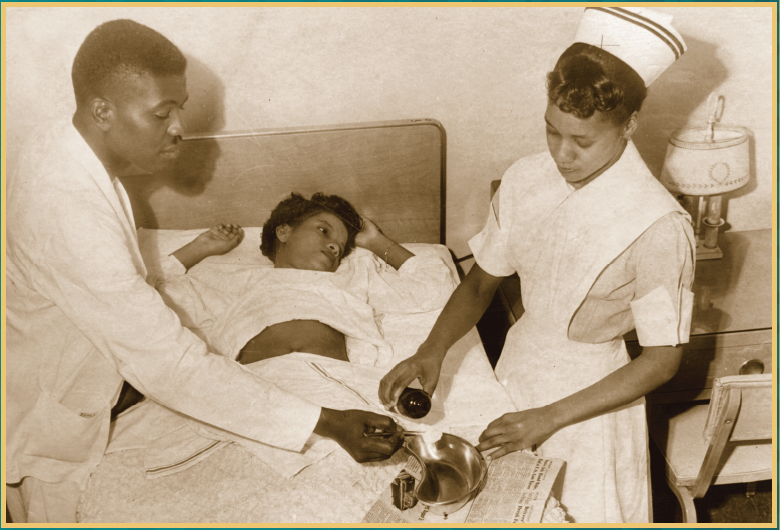

Provident Hospital can claim a number of “firsts” in the history of American healthcare. It was the first private hospital in the state of Illinois to provide internship opportunities for black physicians and the first to establish a school of nursing to train black women. It was one of the first black hospitals to provide postgraduate courses and residences for black physicians and the first black hospital approved by the American College of Surgeons for full graduate training in surgery. Provident also offered an important forum, a proving ground for ideas about black self-determination and institutional survival. “Provident Hospital: A Living Legacy” at the International Museum of Surgical Science is the story of this landmark institution, told through rarely exhibited records, photographs and physical objects (including historic uniforms) from the Hospital’s history. Organized as a collaboration between the Provident Foundation and the International Museum of Surgical Science, “Provident Hospital: A Living Legacy” examines health history and social history as not only parallel but interdependent in this country.

View our online exhibition:

Experiences of the City’s White and African American Populations Diverge

Through most of Chicago’s early history, the experiences of the city’s white and African American populations diverged. Consider the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Most history books describe the fire and resulting damage. But as historian Dempsey Travis points out, the 1871 fire stopped on Harrison Street, and only a small portion of the city’s black dwellings were destroyed. An 1874 fire, seldom mentioned in history books, gutted over 800 buildings, including 85 percent of the city’s black-owned property. More important contrasts in the experience of blacks and whites include the plight of African Americans who required medical care and their systematic exclusion from health care facilities and health professions training. For much of Chicago’s and the nation’s history, until the Civil Rights era of the 1960s, blacks requiring health care were turned away at the hospital door. While this discrimination imposed an impenetrable wall for some people, it emboldened others. In Chicago’s African American community of the 1890s, a new concept arose: a facility that would accept all patients, regardless of race, creed or ability to pay. This is the story of that landmark institution: Provident Hospital. From 1891-1987, the Provident Hospital and Training School, later known as Greater Provident Hospital, the New Provident Hospital and then the Provident Medical Center, served a vital healthcare role for Chicago’s growing black population.

Provident can claim a number of “firsts” in the history of American healthcare. It was the black-owned and operated hospital in America and the first private hospital in the State of Illinois to provide internship opportunities for black physicians. Provident was also the first to establish a school of nursing to train black women. It was one of the first black hospitals to provide postgraduate courses and residencies for black physicians and the first black hospital approved by the American College of Surgeons for full graduate training in surgery. Provident also offered an important forum, a proving ground for ideas about black self determination and institutional survival. Throughout its history, philosophical differences emerged on issues such as black control, the response to institutional discrimination, and how to maintain services. In recent years, Provident’s greatest challenge arose during the 1980s, when the Hospital faced bankruptcy and closure. The federal government stepped in, assumed much of Provident’s debt, and expedited the hospital’s shift from a private, black-run facility to a public facility under the Cook County Bureau of Health Services. This produced sharp differences of opinion, continuing a debate on black self-determination in health care that originated at the time of the Hospital’s founding.

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams

A people who don’t make provision for their own sick and suffering are not worthy of civilization.

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams (1856-1931), the founder of Provident Hospital, was born in Hollidaysburg, PA. His father was a barber who was deeply religious and imparted a sense of pride on his eight children. When his father died of tuberculosis, Daniel was nine-years old. His mother, Sarah Prince Williams, moved the family to Baltimore to live with relatives. Daniel was apprenticed to a shoemaker in Baltimore for three years. By age 17, he had also studied and become a successful barber and lived with the Anderson family in Janesville, WI, where he worked in their barber shop. He attended high school and later an academy where he graduated at the age of 21.

He began his studies of medicine as an apprentice under Dr. Henry Palmer, a prominent surgeon. Dr. Palmer had three apprentices and all were accepted in 1880 into a three-year program at the Chicago Medical College, considered one of the best medical schools at the time. Daniel graduated with an M.D. degree in 1883.

Dr. Williams began practice in Chicago at a time when there were only three other black physicians in the city. He secured an appointment at the South Side Dispensary where he could practice medicine and surgery. Dr. Williams also served as an anatomy instructor at Northwestern University Medical School.

Dr. Williams was acutely aware of the limited opportunities for black physicians in 19th century Chicago. In 1890, Reverend Louis Reynolds, whose sister Emma was refused admission to nursing school because she was black, approached Dr. Williams. This encounter led to the founding of Provident Hospital and Nursing training School in 1891.

Dr. Williams insisted that the physicians at Provident remain abreast of emerging medical discoveries. He himself earned widespread renown as a surgeon in July 1893 when a young man named James Cornish entered the hospital with a stab wound to the heart. Dr. Williams performed a new surgical method to repair a tear in the lining of Cornish’s heart, saving his life and while conducting one of the first successful surgeries to the organ on record.

From 1894-1898, Dr. Williams served at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington D.C. In December 1895, he helped organize the National Medical Association (NMA), which was, at the time, the only national organization open to black physicians. He was appointed the organization’s first Vice President. In 1898, Dr. Williams returned to Provident where he became chief of surgery and in 1902 performed another breakthrough operation – successfully suturing a patient’s spleen.

In 1900, Dr. Williams was invited to become a visiting professor of surgery at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, TN, one of two black medical schools in the country, where a decade before there had been none. Dr. Williams was a Charter Member of the American College of Surgeons, founded in 1913, and its first black fellow.

Despite his national prominence, Dr. Williams faced differences with Provident’s administrators and physicians, principally over hospital privilege issues. Yet, he continued working at Provident and maintained an active national travel schedule until 1912 when he resigned from Provident after being appointed attending staff surgeon at St. Luke’s Hospital in Chicago. He served as an attending staff surgeon at St. Luke’s until 1926, and remained in active practice in Chicago until he suffered a stroke in 1926. He then moved to Idlewild, MI where he lived in retirement until his death in 1931.

The Early Years: 1891 – 1920s

Within the United States, racial discrimination in health care runs deep. It is rooted in the treatment accorded blacks throughout the period of slavery Slave hospitals, the first health care facilities developed for blacks on large Southern plantations were intended to separate sick from healthy slaves.

At the end of the Civil War, in the 1870s, there were about 7,000 African Americans living in Chicago. By 1889, it became the second city in the country to reach a million inhabitants, and the black community had grown to approximately 15 ,000. Most of these residents were low-income laborers who lived in conditions of poverty Health problems were prevalent. Racial customs and mores restricted blacks’ access to most hospitals. In the North, black patients were often denied admission or were accommodated, almost universally, in segregated wards.

In 1889, Emma Williams, a young woman who aspired to be a nurse, was denied admission by each of Chicago’s nursing schools on the grounds that she was black. Her brother, the Reverend Louis Reynolds, approached the respected black surgeon, Dr. Daniel Hale Williams for help. Unable to influence the existing schools, they decided to launch a new nursing school for black women

Donations were collected. Rallies were scheduled on Chicago’s south and west sides. One of the most important early contributions came in 1890 when clergyman Reverend Jenkins Jones secured a commitment from the Armour Meat Packing Company for the down payment on a three-story brick house at 29th and Dearborn. This building, with 12 beds, became the first Provident Hospital. Black residents, workers, employers, public officials, church leaders, and civic leaders contributed heavily to opening and sustaining the facility.

At that time, there were many health perils in everyday life in Chicago. In 1893, for example, 1,033 Chicagoans died in a smallpox epidemic. As Chicago’s institutions began to take shape, so did the city’s efforts to maintain public health. In 1892, the City of Chicago began milk inspection to reduce milk-borne infections. In 1896, the first diphtheria antitoxin was dispensed to reduce the deaths from this disease.

In 1894, when Emma Reynolds and three of her classmates became Provident’s first nursing school graduates, the need for health care workers was very high. However, discrimination limited their opportunities, as the City visiting nurses association would not hire any of the Provident graduates. In response, in 1897, the hospital launched its own visiting nurse service that provided over 990 visits to nearly 200 homes during the first year of operation.

As the demand for medical care grew, the Provident board initiated planning to expand. An 1896 funding campaign raised sufficient funding to construct a new building on donated land at 36th and Dearborn. The effort was helped by abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who gave a public lecture in Chicago and presented a donation at the Hospital site to Dr. Williams.

In 1918, Chicago experienced an influenza epidemic that on one day caused 381 deaths across the city The following year witnessed a racially motivated calamity A South Side race riot, the second in a month, began when a black teenager swam to a “white beach.” He was stoned and subsequently drowned. The ensuing four days of fighting resulted in 33 deaths, 306 injuries, and 2,000 people homeless. The Provident was busy day and night.

“Germs Have no Color Line”

Throughout this time, segregation was a common practice in much of the North and it was thoroughly entrenched in the South. The black community responded by forming new entities that afforded parallel opportunities. The black hospital movement, which eventually included over 200 hospitals, began to grow across the country. In 1895, the National Medical Association (NMA) was organized to promote the general interests and scientific advancement of black physicians, dentists and pharmacists.

In this context, in 1928, Provident’s Dr. Hall met with Dr. Franklin Mclean of the University of Chicago to discuss a potential affiliation for medical education. The University hospital’s policy, which prohibited admission of black patients, was acknowledged by Dr. Mclean to be both an embarrassment and an impediment to training black medical students. They discussed developing a new model for black medical education.

Provident’s charter was amended in 1931 to increase the number of board members and to add medical education to the official purpose: “to conduct a hospital for the care of the sick, a training school for medical students, interns and postgraduate medical students, and a training school for nurses.” Mr. Jackson urged the Provident trustees to continue to maintain black control However, Dr. N. J Blackwood, a white physician and retired naval admiral, was named Provident’s medical director.

Provident Hospital was especially vulnerable during periods of economic downturn. During the Depression of the 1930s, the hospital continued to treat all incoming patients, regardless of race, ethnicity or ability to pay. Tensions between Provident and other organizations continued to build. There was dissension between some physicians and administrators regarding Provident’s commitment to black control. In 1934, the Cook County Physicians Association (a local black medical society) began a campaign against the placement of a black medical student from the University of Chicago in a clerkship at Provident. They argued that black and white students should be subject to the same assignments.

During this period, health conditions within communities served by Provident were poor. The death rate for blacks in 1937 was 285 per 100,000, about three times higher than that of the general population. Tuberculosis was a leading cause of death and illness. It was spread by close contact, substandard housing and poor health conditions.

In 1938, the American College of Surgeons had fully approved Provident for graduate medical training in surgery Provident became one of nine Illinois hospitals accredited for surgical training. The Hospital had acquired a national reputation as a teaching hospital and it was one of only several hospitals in the country where black physicians could receive graduate training. While limited numbers of black men and women were admitted to medical schools and graduated with a medical doctor degree, most hospitals would not accept them for the next phase of training that allowed them to become medical specialists. Thus, The Provident’s ability to have certified programs for residents in many therapeutic areas was a critical issue for black physicians.

The Civil Rights-Era through the Present Day

Following the end of World War II, black leaders and their allies fought to bring an end to racial segregation. Hospital segregation, which had restricted the admitting and staff privileges of minority physicians-and relegated black patients to segregated wards came under pressure to change.

In 1950, the American Medical Association urged its state chapters to allow black physicians to join. However, the National Medical Association, representing black physicians, continued to provide a strong voice for black professionals. In 1951, the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses voluntarily disbanded and urged its members to join the American Nurses Association (ANA). At that time, 330 nursing schools admitted students regardless of race, and all but five state nursing associations allowed black nurses to join. The Cook County Board had voted to admit black women into their nursing school in 1945.

In 1960, the black population of Chicago represented almost 23 percent of the City’s residents. Provident drew from a large black population with limited services, despite generally poorer health status and higher disease rates than the city’s overall population. The landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 mandated that no person could be subject to discrimination or excluded from the benefits of any program receiving federal financial assistance based on race, color, or national origin. This was interpreted to apply to all hospitals, which had become eligible for the new federal health insurance programs for the elderly (Medicare) and low-income persons (Medicaid) in 1965. The integration of health care facilities was a critical step forward, but there were negative consequences for institutions that had served predominantly black communities.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Provident Hospital continued to provide services, but financial constraints limited the upgrades that were needed in equipment and facilities.By the mid-1970s, consensus was reached that the hospital building needed replacement. In 1974, a controversial arrangement with Cook County Hospital was instituted to allow the County to refer patients to Provident and to assist new hospital planning. In 1978, Congressman Ralph Metcalfe of Chicago announced that two federal agencies had committed major grants and loans to move the development of a new 300-bed hospital forward. Provident Medical Center opened at 500 East 51st Street in May 1982.

Provident Medical Center offered training for licensed practical nursing students from Chicago State University and the City Colleges of Chicago. However, mounting financial strains continued to plague the hospital, threatening its continuance. Increasing debt led to a series of efforts to sustain Provident, including developing an alliance with Cook County Hospital, and other public and private financing plans. None of these efforts were successful and the hospital declared bankruptcy in July 1987. Provident Hospital closed in September 1987.

Efforts to salvage the hospital were often heated and left all parties – the community, former employees, and black leaders – in consternation. The interest in reopening Provident Hospital remained a priority for many individuals. Community groups and others tried to raise both funding and political support to reopen the hospital.

After considerable investment in upgrading the physical plant, Provident Hospital reopened in August 1993. The Hospital’s traditional medical education role was reestablished in 1994 through an educational affiliation with Loyola University’s Stritch School of Medicine. While no longer considered a black-run hospital, Provident continues to serve the health needs of the community, including a variety of health outreach efforts.

Provident Hospital was often the safest – and sometimes the only – place to go.

Timuel Black, Activist and Educator

Graphic design by Amelia Fawcett